In college, I always enjoyed a good philosophy class. Such classes had this aura about them, as though I was about to gain access to some hidden, pure truth. And then, after an hour or so of class of steeping in higher realities of being, I would go grab lunch or head to practice. Such ideas seemed to have little applicability to the rest of my day, except for conversation fodder.

Of course, one would assume that people who sit around thinking deeply all day would have some lock on the truth, but if that were true, that sure didn’t come across during class. All this thinking power and inference making and deductive reasoning and yet people still end up on diametrically opposite sides of various issues and questions. Is there a God? What is the good? (what does that mean?) Some philosophy professors made it completely clear which side they supported and made every effort to convince their students to agree or else feel humiliated. Other professors brilliantly erected and demolished competing arguments just to keep their students’ heads swirling.

In my Philosophy of Law class, one of the questions my professor explored was the question of whether lawyers are morally obligated to zealously advocate for their clients even if that meant doing seemingly immoral things to win their case. On the first day of discussing this topic, he made a rock-solid case for zealous advocacy. Impeccable. Brilliant. Pure Reason! I’m pretty sure he had us all convinced or at least feeling pretty stupid for thinking otherwise. During the next class though, he completely laid waste to the argument he made the class before and proceeded to erect an argument for why lawyers do not have a moral obligation to zealously advocate for their clients. Again, Impeccable, Brilliant, Pure Reason!

Wait…huh? What’s going on here? Which is it?

Early in my college career with my faith growing afresh, apologetics played a crucial role in my intellectual life. I was discovering that apologetics, which is the philosophical and intellectual defense of Christianity, helped address some of the troubling questions that cropped up in the world of faith. I would read some apologist’s argument for God’s existence, or how an all-powerful, all-knowing, good God could be compatible with a world filled with evil, and I would think to myself, “Yeah, who could possibly refute this? Impeccable! Brilliant!” And then I would read some atheist’s rebuttal argument, and if I were being honest with myself, I’d think, “That troublingly sounds pretty convincing too.” I wouldn’t use the word “brilliant,” but then again, someone without a Christian bias—an atheist bias perhaps—probably would use the word “brilliant” to describe such an argument.

So what are we supposed to believe? Or rather, what do we believe?

It seems to me that we tend to believe what we want to believe. We humans are pretty good at constructing arguments to support whichever position we want to take on whichever issue we’re discussing. Whether we are willing to admit it or not, every argument starts with an assumed premise. Even empiricism, which claims to rely totally on experience without any assumptions, relies on the assumption of its own validity. We simply cannot escape the necessity of taking things on faith, usually a great deal for that matter—theist, atheist, Christian, Buddhist, Democrat, Republican. In fact, it’s quite possible that the degree of certainty we feel about our beliefs and the clarity of our reason is nothing more than an illusion to aid in our survival, which, if true, would delegitimize this whole sentence, and this whole blog post.

Fortunately the futility of philosophy has not left me as a total skeptic, or a total flake; I still believe things. But such exercises have liberated me from the bondage of having to prove some of the most important things that I believe. I don’t feel the need to prove that my parents truly love me; I simply accept it as given. And I don’t have to prove my Jesus and the purpose and fullness He gives my life. I just have to choose to live in that fullness.

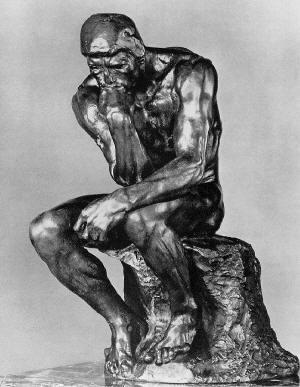

I’ve discovered that if we spend too much time in the ivory tower, then we won’t get around to the business of living each day to its fullness and of hoping for tomorrow.

No comments:

Post a Comment