Tuesday, May 31, 2011

Lesson 5: Coming soon!

So, my life has suddenly become exceedingly busy. Looks like I won't be able to squeeze in my last college lesson before the month is up. But, I did want to create this place-holder post in order to keep all my Lesson posts in the month of May. It works better for organizational purposes. And with that, back to the whirlwind...

Friday, May 27, 2011

Lesson 4: We Believe What We Want to Believe

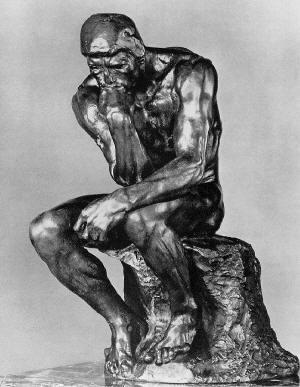

In college, I always enjoyed a good philosophy class. Such classes had this aura about them, as though I was about to gain access to some hidden, pure truth. And then, after an hour or so of class of steeping in higher realities of being, I would go grab lunch or head to practice. Such ideas seemed to have little applicability to the rest of my day, except for conversation fodder.

Of course, one would assume that people who sit around thinking deeply all day would have some lock on the truth, but if that were true, that sure didn’t come across during class. All this thinking power and inference making and deductive reasoning and yet people still end up on diametrically opposite sides of various issues and questions. Is there a God? What is the good? (what does that mean?) Some philosophy professors made it completely clear which side they supported and made every effort to convince their students to agree or else feel humiliated. Other professors brilliantly erected and demolished competing arguments just to keep their students’ heads swirling.

In my Philosophy of Law class, one of the questions my professor explored was the question of whether lawyers are morally obligated to zealously advocate for their clients even if that meant doing seemingly immoral things to win their case. On the first day of discussing this topic, he made a rock-solid case for zealous advocacy. Impeccable. Brilliant. Pure Reason! I’m pretty sure he had us all convinced or at least feeling pretty stupid for thinking otherwise. During the next class though, he completely laid waste to the argument he made the class before and proceeded to erect an argument for why lawyers do not have a moral obligation to zealously advocate for their clients. Again, Impeccable, Brilliant, Pure Reason!

Wait…huh? What’s going on here? Which is it?

Early in my college career with my faith growing afresh, apologetics played a crucial role in my intellectual life. I was discovering that apologetics, which is the philosophical and intellectual defense of Christianity, helped address some of the troubling questions that cropped up in the world of faith. I would read some apologist’s argument for God’s existence, or how an all-powerful, all-knowing, good God could be compatible with a world filled with evil, and I would think to myself, “Yeah, who could possibly refute this? Impeccable! Brilliant!” And then I would read some atheist’s rebuttal argument, and if I were being honest with myself, I’d think, “That troublingly sounds pretty convincing too.” I wouldn’t use the word “brilliant,” but then again, someone without a Christian bias—an atheist bias perhaps—probably would use the word “brilliant” to describe such an argument.

So what are we supposed to believe? Or rather, what do we believe?

It seems to me that we tend to believe what we want to believe. We humans are pretty good at constructing arguments to support whichever position we want to take on whichever issue we’re discussing. Whether we are willing to admit it or not, every argument starts with an assumed premise. Even empiricism, which claims to rely totally on experience without any assumptions, relies on the assumption of its own validity. We simply cannot escape the necessity of taking things on faith, usually a great deal for that matter—theist, atheist, Christian, Buddhist, Democrat, Republican. In fact, it’s quite possible that the degree of certainty we feel about our beliefs and the clarity of our reason is nothing more than an illusion to aid in our survival, which, if true, would delegitimize this whole sentence, and this whole blog post.

Fortunately the futility of philosophy has not left me as a total skeptic, or a total flake; I still believe things. But such exercises have liberated me from the bondage of having to prove some of the most important things that I believe. I don’t feel the need to prove that my parents truly love me; I simply accept it as given. And I don’t have to prove my Jesus and the purpose and fullness He gives my life. I just have to choose to live in that fullness.

I’ve discovered that if we spend too much time in the ivory tower, then we won’t get around to the business of living each day to its fullness and of hoping for tomorrow.

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

Lesson 3: History is not what happened, history is what we say happened.

Before college, history, as I understood it, was very simple. History was a set of objective facts compiled into official text books. All you had to do was read the text book to find out “what happened.”

In college though, I discovered this fancy concept known as historiography, which is “the writing of history.” Historiography is a form of history all its own. For example, not only is the complicated and divisive American Civil War part of history, but so is the way historians have written about it. Historians from the North wrote about the Civil War differently than historians from the south, and historians living in 1870 wrote about it differently than historians living in 1970. No matter when or where a historian is from, they just can’t escape their own perspectives and biases and prejudices and cultural values. And so, Civil War historiography varies considerably. Now things like dates and the number of men in such-n-such brigade don’t elicit much debate, but questions like, “What caused the Civil War?” or “Who was to blame for such-n-such policy?” are far more complicated.

A few years ago a friend encouraged me to read a particular book on Christian church history from the first century to the present. He said something to the effect of, “This book tells the real facts.” Of course, with Biblical and church historians ranging from conservative fundamentalist historians to secular atheistic historians, I was a bit skeptical that this one book had successfully encapsulated all the REAL facts to the exclusion of all the biased non-facts. But the book sounded interesting, so I opened up to the introduction.

The author of this book acknowledged the many controversies and differences of opinion that have colored Biblical and church scholarship, but he insisted that rather than mere personal opinion, his account would be objective (aka this is what REALLY happened). I had read enough, and I placed the book back on the shelf to continue collecting dust.

What are the REAL facts anyway? Are the real facts what the writers of primary source documents said, who of course had their own biases and prejudices, or are the real facts what scholarly writers of secondary source documents say, who also have their own biases and prejudices, or are the real facts contained in high school text books? (I hear that Texas recently adopted the use of text books which all but completely eliminate Thomas Jefferson from its chapters on early United States history because people on some Texas educational board didn’t like Jefferson ’s ideological values. Bias and prejudice? Check.).

Everyone has biases and prejudices, from Herodotus to that really arrogant church historian; and I have biases and prejudices too. A historian, or anyone for that matter, is far more credible when he admits what his biases are than when he pretends to be objective.

Now I’m no relativist; I believe certain things did indeed happen a certain way. And I’m no epistemological skeptic; I believe we can access the past. But I recognize that it is difficult and some debates just don’t go away very easily, and for good reason. For most of human history, we simply don’t have any video type records of what happened when, where, and why. So ultimately history is not “what happened,” rather history is “what we say happened.” And that story is constantly evolving and being refined.

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

Lesson 2: Don’t be a heretic in the truth!

In my John Milton class, we read Milton

And so Milton

He argues that nothing should be censored and that every written piece should be allowed to stand on its own. If a given piece contains fallacious reasoning or weak arguments, then any rational person would be able to recognize such fallacies and reject the argument accordingly. He argues that if everything were freely published, than the truth would win out as rational people read and evaluate opposing arguments and writings. Milton England

During the revolution, the crown was overthrown, Cromwell ascended to the Protectorate, and Milton Milton

But Milton Milton

Clearly, it’s bad to believe the wrong things for the wrong reasons, but equally unjustified according to Milton Milton

This sounds ridiculous, but people do this all the time. Perhaps they merely parrot what one church’s denominational doctrine says and disregard opposing viewpoints because this one denomination or tradition, they believe, somehow succeeded in correctly understanding all of the Bible’s passages. Perhaps they only get their news from one cable network because they figure that all the rest are biased and unreliable. Perhaps they perfectly align themselves with their political party of choice policy-for-policy because this party is always right (or at least, always more right than the other party).

Are things true because we believe them, or do we believe things because we think they are true? If what’s true is true irrespective of our beliefs, then we should have no qualms about reading and considering fair arguments that cast the opposing view in the best light possible. No cable network should be off limits whether it is MSNBC or Fox News. No book should be off limits whether it is God Delusion or the Bible.

Figuring out what is true isn’t supposed to be easy. If it does seem easy, then there is a good chance that what we believe to be true, isn’t. And if we did get lucky and believe the right thing by happenstance without the necessary intellectual rigor, then we’re still just heretics in the truth.

Friday, May 6, 2011

Lesson 1: Shooting the Albatross is a Good Thing

One of the more twistedly beautiful poems I read in college was “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In the poem, a strange, old man stops an arriving wedding guest outside a church to tell him an enigmatic tale from his seafaring days. The wedding guest doesn’t have time for a lengthy and random story, but is rendered powerless to resist the old man’s aura and oratorical cadence.

And it’s a tale indeed. After winding up in some less-than-desirable circumstances out at sea, the mariner and his fellow sailors are visited by an albatross. This seemingly innocent creature has little else of an agenda other than to offer company to the crew and to play about. And yet, in an act of inexplicable cruelty, the mariner shoots the albatross with his crossbow.

What ensues is a bizarre series of ill-fortuned, illusory events that terrify the mariner beyond imagination: he finds himself floating upon a rotting, burning sea parched and starving with slimy creatures all around, haunting spirits like “Nightmare Life-In-Death,” phantoms, and a crew that dies and rises again as zombie creatures. For part of his penance, the mariner must wear the dead body of the albatross around his neck as a reminder of the needless evil and woe that he has wrought.

After an ageless stretch of time, the mariner finally gains insight into both his deeds and his own self. He survives these tormenting terrors and lives out his days a sadder but wiser man.

At some point that overly simplistic, childlike manner of literary interpretation kicks in and we find ourselves asking that cliché question, “What’s the moral of the story?”

Many would say, “Don’t shoot innocent albatrosses,” or perhaps, “Learn from others’ mistakes.” After hearing out the mariner’s gruesome tale, how could one possibly think that it would be a GOOD idea to shoot the albatross?

And yet it is clear that the mariner’s harrowing life transformation would not have been possible had he not shot the bird. Some lessons in life—deeply significant and personal lessons—just can’t be learned by heeding instruction, but rather must be learned through experience. Some truths about life just can’t be truly understood unless you shoot the albatross.

Which reminds me of a shameful moment several years ago when I unwittingly shot the albatross of my pride to smithereens. After an ageless stretch of time waiting at a walk-in clinic to receive an allergy shot, the nurses notified me that my serum was not in the refrigerator. Through my mind began to race all the inconvenience and frustration that would result from this act of carelessness. I demanded that they look again. After another failed attempt, they suggested that I go home and look in my home refrigerator. I was rude and short with them; I told them I would, but that it wouldn’t be there. I knew it wasn’t in my home refrigerator. And so I drove home just waiting to be vindicated, marched up the steps, through the kitchen, opened the refrigerator door, and just as I expected…MY ALLERGY SIRUM?!? NO! It couldn’t be!

And there hung that dead albatross around my neck. As I drove back to the clinic with an apology note, my serum and a half-baked idea of what I was going to say, feeling like I should be wearing a paper bag over my head, I remember smiling and thanking God that he had blown up my pride, at least for the moment. I thought I already understood such concepts as humility, patience, personal fallibility, etc. But some things in life simply can’t be learned or understood apart from experience. Often in life you learn humility by first being prideful, patience through impatience, personal fallibility by making stupid choices. I can only be thankful that the nurses were more gracious to me than I had been to them, especially considering that they were about to stick a needle in my body.

This is one of my albatross stories. If in some way my story is instructive to others like the mariner’s possibly was, then great. But I think that far more likely our stories are a beautiful reminder that, for our own personal development, it just may be good to shoot the albatross from time to time.

Monday, May 2, 2011

Five Lessons From My College Education

Later this month, I will mark one of life’s big mile stones: college graduation. (Actually I’m only pretending to graduate. I still have one class to go this Summer, and I wasn’t actually enrolled during this year’s fall and spring semesters due to collegiate athletics and career ending injuries and unexpected turns and twists, so it’s a little anticlimactic—but it is a symbolic victory with the real victory assured to come in August.)

As I reflect on the last five years of my life and how much I have changed and grown into the man that I am, in some ways it is hard to remember who I was in high school. I suppose only the people whom I haven’t seen since high school could comment on whether I’m the same Jay Bilsborrow or a different Jay Bilsborrow, or perhaps a nuanced Jay Bilsborrow.

While at William and Mary, I was (still am?) a good ol’ fashioned liberal arts humanities major, which means other than being a better reader and writer, I am not coming away with any practical skills or knowledge (good thing I’m going to law school! Ha!).

So other than some interesting information about John Milton and the Crusades and Symbolic Logic, what did I learn from college? While by no means an exhaustive list, I have identified the 5 Lessons I Learned in College (4 from my studies and 1 from athletics). During May, I am going to blog on each lesson throughout the month. Stay tuned.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)